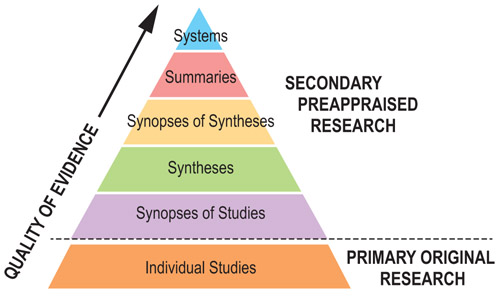

Secondary evidence

The different types of secondary research, ranked in order of increasing usefulness to busy clinicians, are described in more detail below.

Select each section of the pyramid to see the detailed definitions.

Systems

These are decision support systems that match information from individual patients with the best evidence from research that applies to the clinical situation. These integrated systems are not yet well developed; the ideal evidence-based clinical information system would concisely summarise all relevant research evidence about a clinical problem and automatically link this to an individual patient’s situation through an electronic medical record. The system would ideally be updated as new evidence became available. The clinician and the patient would then have the benefit of current best evidence.

Summaries

These integrate the best available evidence from the lower levels of the pyramid, and draw on systematic reviews wherever possible to provide a full range of evidence concerning management options for a given health problem. Unlike the lower layers of the pyramid, summaries bring together the full range of options, not just one aspect.

- Sources

BMJ and Best Practice, UpToDate, Cochrane Clinical Answers, Joanna Briggs Institute.

- Example

Priyanka Pamaiahgari, BDS. Delirium: Pharmacological Management.The Joanna Briggs Institute EBP Database, JBI@Ovid. 2018; JBI14501. [15]

This 3 page summary reviews evidence from multiple systematic reviews and meta-analyses including numerous source trials.

Synopses of syntheses

These are carefully edited, usually short – typically 1 to 2 pages – structured descriptions and critical commentaries of systematic reviews. They are often accompanied by a commentary that addresses the methodological quality of the synthesis and the clinical applicability of its findings.

Busy clinicians do not always have the time to review detailed systematic reviews, a synopsis that summarises the findings of a high-quality systematic review can often provide sufficient information to support clinical action. Often the title provides enough information to allow the decision maker to proceed. The advantage of finding a relevant synopsis of a synthesis is that the synopsis provides a convenient summary of the corresponding synthesis.

- Sources

- Joanna Briggs Institute, Cochrane Clinical Answers (in Cochrane and BMJ Best Practice), reviews in DARE (the Database of Abstracts of Reviews of Effectiveness, Cochrane Library), within monographs in various databases e.g. UpToDate, BMJ Best Practice and in articles indexed in MEDLINE, Embase etc.

- Example

- Burch J, Tort S. What are the benefits and harms of antioxidant vitamin and mineral supplements used to prevent age‐related macular degeneration?. Cochrane Clinical Answers. 2017. [16]

This synopsis summarises a systematic review: Evans JR, Lawrenceson JG. Antioxidant vitamin and mineral supplements for preventing age-related macular degeneration. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2017 Jul 30. [17]

Vitamin E, vitamin C, beta-carotene, and multi-vitamins showed no benefit in preventing age-related macular degeneration, and all except vitamin C were associated with adverse effects.

Syntheses

These can be found in the databases of systematic reviews. Syntheses systematically bring together and distil the best evidence to answer particular clinical questions. Generally, they ‘pool’ the results of several randomised controlled trials or meta-analyses on the same clinical problem.

- Sources

- The Cochrane Collaboration (provides the world’s single best source of systematic reviews). Systematic Reviews are also available from the Joanna Briggs Institute.

- Example

- Lundh A, Lexchin J, Mintzes B, Schroll JB, Bero L. Industry sponsorship and research outcome. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2017 Feb 16. [18]

Synopses of studies

These studies provide structured abstracts of individual, high quality, clinically relevant studies. The advantage over the original study is the assurance that the original has been screened for quality and the summary although brief is often sufficiently detailed to inform clinical practice.

- Sources

- ACP Journal Club, Evidence-Based Nursing journal, International Journal of Evidence - Based Healthcare ( Formerly : JBI Reports ) journal

- Example

- Time window for mechanical thrombectomy after acute ischemic stroke. UpToDate. Wolters Kluwer. 2018. [19]

This brief summary of two trials – DAWN and DEFUSE 3 - was graded a 1B recommendation. This is explained by UpToDate:

‘Grade 1 recommendation is a strong recommendation. It means that we believe that if you follow the recommendation, you will be doing more good than harm for most, if not all of your patients.

‘Grade B means that the best estimates of the critical benefits and risks come from randomized, controlled trials with important limitations (e.g. inconsistent results, methodologic flaws, imprecise results, extrapolation from a different population or setting) or very strong evidence of some other form. Further research (if performed) is likely to have an impact on our confidence in the estimates of benefit and risk, and may change the estimates.’

One of these trials – DAWN – was also the subject of an ACP Journal Club summary:

- Mai LM, Ocskowski W. Late thrombectomy reduced disability in acute stroke with mismatched clinical deficit and infarction volume. ACP Journal Club. 2018 168(4): JC17 [20]

The authors conclude ‘DAWN, an industry-sponsored trial, confirms a large improvement with mechanical thrombectomy in highly selected patients … Successfully treating stroke beyond 6 hours extends the currently established "time window" approach to treatment of hyperacute stroke - a revolutionary result given the notion that "time is brain".' [21]

From this level down in the Pyramid, critical appraisal is essential.

Individual studies

These studies are investigations that collect original (primary) data from patients, e.g., randomised controlled trials, observational studies, series of cases, etc. They are the building blocks of all secondary evidence.

- Sources

- MEDLINE, Embase, PsycINFO.

- Example

- Cushman WC, Evans GW, Byington RP et al. Effects of intensive blood-pressure control in type 2 diabetes mellitus. ACCORD Study Group, New England Journal of Medicine. 2010; 362(17):1575-85. [22]